Abstract

The tragic mass shooting at Campus Risbergska in Örebro, Sweden, by Rickard Andersson, underscores the urgent need for innovative approaches to prevent radicalization. This analysis, using the evidence-based MOSAIC (Meaning-Oriented Social And Individual Change) model of radicalisation, offers invaluable insights into Andersson’s journey from meaning-making failures and social isolation to violent extremism. The analyses with the MOSAIC model reveals five distinct phases of radicalization, from pre-radicalization to extremist outcomes, providing a roadmap for early intervention. Andersson’s case highlights critical factors, including economic inequality, academic struggles, and long-term unemployment, that contributed to his sense of being unable to live a meaningful life and contribute to a meaningful world. His struggles to find meaning led to his immersion in extremist white supremecist ideologies, and ultimate commitment to a radical narrative that culminated in the devastating attack. By understanding the role of meaning-making in radicalization, local authorities and governments have a unique opportunity to implement targeted prevention strategies. These may include meaning-oriented education programs, community engagement initiatives, and improved mental health support systems. Investing in this approach can play a crucial role in building resilient communities and preventing future tragedies, transforming this devastating event into a catalyst for positive societal change.

Aim and Methodology

This text aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of Rickard Andersson’s radicalization process leading to the tragic mass shooting at Campus Risbergska in Örebro, Sweden, on February 4, 2025. By applying the MOSAIC (Meaning-Oriented Social And Individual Change) model, we seek to offer insights into the complex interplay of personal, social, and societal factors that contributed to this act of violent extremism. This analysis is intended to inform policymakers and relevant authorities about the nuanced nature of radicalization processes and to provide evidence-based recommendations for prevention and intervention strategies.

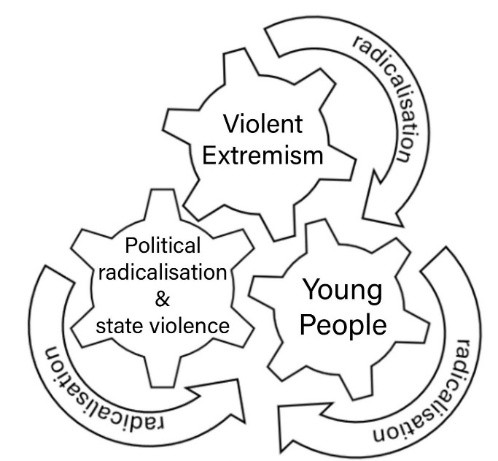

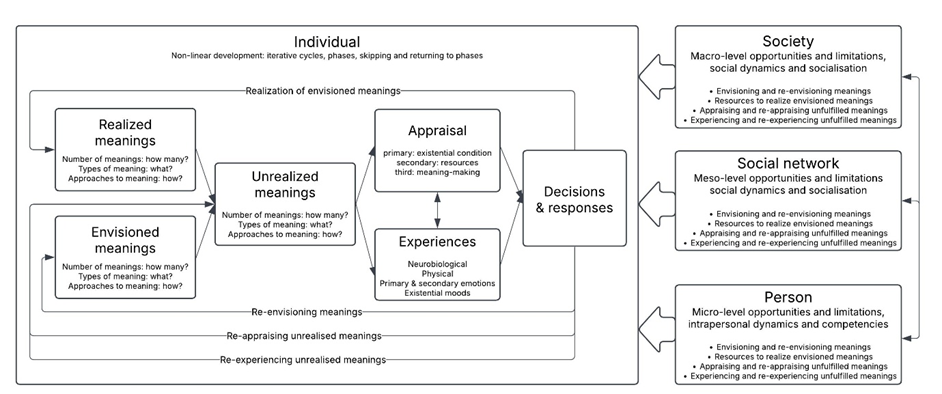

The MOSAIC model, developed by Vos and colleagues identifies five distinct phases in the radicalization process:

- Meaning foundations (Pre-radicalization)

- Meaning search (Initial exposure and explorations)

- Meaning immersion (Engagement with radical network)

- Meaning commitment (Solidification of radical narrative)

- Extremist outcomes (Preparation and execution)

Within each phase, the model examines how an individual envisions a meaningful life and world, how they try to realise this, and how they experience, appraise and respond to unrealised meanings, under influence from society, social networks, and personal circumstances. As individuals may experience repeated failure to realize the meaningful life and world they had envisioned, they may shift towards using more radical methods to realize their meanings, develop more radical envisioned meanings, and radicalise reappraise the cause and solutions to their failures.

This article was written with the help of AI Claude that was trained with the MOSAIC model, which serves as an example of how the model and the app could be used to quickly analyze and respond to emerging cases of radicalization. By applying this model to Rickard Andersson’s case, we can gain valuable insights into the factors that contributed to his radicalization and identify potential intervention points.

Analysis of Rickard Andersson’s Radicalization Process

Phase 1: Meaning foundations (Pre-radicalization)

Society

- Andersson grew up in Örebro, Sweden, a mid-sized city undergoing economic transition from industrial to service-oriented sectors.

- Sweden experienced increasing economic inequality since the mid-1980s (OECD, 2015), potentially creating a sense of relative deprivation.

- Changes in the labor market, including the decline of blue-collar union influence (Svallfors, 2016), may have contributed to feelings of disenfranchisement.

- Andersson grew up in what a relative described as a “prosperous area” (Avaz.ba, 2025), suggesting a contrast between his personal circumstances and his surroundings.

Network

- As a child, Andersson was part of a group of boys who played and gamed together (Aftonbladet, 2025), indicating initial social connections.

- Over time, he became increasingly isolated, described as a “recluse” and “loner” by relatives (BBC News, 2025; The Independent, 2025).

Person

- Born in 1989 as Jonas Simon to Swedish parents (Expressen, 2025).

- Struggled academically, attending Navets skolen for nine years without passing a single subject (Aftonbladet, 2025).

- Later attended Wadköpings utbildningscenter but never completed high school, passing only history, psychology, and an aesthetic subject while failing seven others (Aftonbladet, 2025).

- Moved out of his parents’ home in 2010 at age 21 (Aftonbladet, 2025).

- Had no taxable income since 2014, never held a state or municipal job, and never took out student loans (Expressen, 2025).

- Had possible mental health issues, as mentioned by relatives (BBC News, 2025; The Independent, 2025).

Envisioned meanings

- Likely envisioned a life of academic achievement, stable employment, and social connections within Swedish society.

Realized meanings

- Academic failure and social disconnection.

- Sense of not meeting societal expectations.

Unrealized meanings experiences & appraisal

- Expectations of success and belonging in Swedish society were not met.

- The gap between his envisioned life and reality likely led to feelings of frustration and resentment.

Phase 2: Meaning search (Initial exposure and explorations)

Trigger event

- Repeated rejection from military service (The Independent, 2025).

- Long-term unemployment, with no taxable income since 2014 (Expressen, 2025).

- Changed his name to Rickard Andersson in 2017, possibly indicating a desire for a new identity (Expressen, 2025).

Unrealized meanings experiences & appraisal

- Intensified feelings of failure and rejection by societal institutions.

- The continued disconnect between his desired life and reality may have intensified feelings of alienation and anger.

Reappraise via open-minded exploration of perspectives

- Possibly began exploring alternative ideologies or worldviews online.

- Andersson likely reappraised societal issues through the lens of extremist narratives, viewing immigration and cultural changes as threats to his identity.

Re-envision meaning by exploring new examples, types and priorities

- May have started considering extremist narratives that offered simple explanations for his struggles.

- Andersson probably began re-envisioning his role as a potential “defender” of his perceived threatened culture or identity.

Realize meanings via adaptive coping

- Obtained a hunting license and legally owned multiple hunting rifles (The Independent, 2025; SVT, 2025).

- Was interested in ice hockey and enjoyed driving, considering becoming a truck driver at one point (Expressen, 2025).

Phase 3: Meaning immersion (Engagement with radical network)

Unrealized meanings experiences & appraisal

- Continued unemployment and social isolation likely intensified feelings of alienation and anger.

- Mental health problems, combined with social isolation, likely intensified his search for meaning and significance (Bhui et al., 2014).

Reappraise by conforming to network narrative

- Likely began viewing societal issues entirely through an extremist lens, reinforcing his radicalized worldview.

- Sweden’s political discourse increasingly focused on immigration-related issues, potentially reinforcing Andersson’s grievances.

- Media framing of integration challenges may have contributed to a polarized public debate (Rydgren & van der Meiden, 2019).

Re-envision by focusing on social and abstract meanings

- Andersson’s vision likely shifted towards a role as a significant actor in a larger ideological struggle, possibly seeing himself as a “warrior” or “martyr” for his cause.

- Probably re-envisioned violent action as a means to achieve significance and make a lasting impact on society.

Realize meanings (mainly social) via network

- While specific information about Andersson’s involvement with extremist networks is not available, research suggests that online communities often play a crucial role in reinforcing radical beliefs (Koehler, 2022).

- Deeper engagement with extremist content and potentially like-minded individuals online may have provided a sense of purpose and significance.

Network social dynamic

- Family members noticed a deterioration in his mental state, reporting that “He didn’t like gatherings. It irritated him. He wasn’t with his parents for Christmas. He wasn’t mentally well” (Avaz.ba, 2025).

- Although Andersson acted alone physically, his radicalization process may have been reinforced by online extremist communities or echo chambers that validated his beliefs (Koehler, 2022)

Phase 4: Meaning commitment (Solidification of radical narrative)

Unrealized meanings experiences & appraisal

- The persistent gap between his radicalized vision and his actual life circumstances may have fueled a desire for drastic action.

- The final disconnect between his extremist vision and the reality of his actions may have manifested as a sense of inevitability or destiny.

Reappraise via fusion of personal meanings with network narrative and/or abstract ideals

- Andersson likely reappraised past events and current societal issues entirely through an extremist lens, reinforcing his radicalized worldview.

- He likely reappraised the value of human life, justifying potential victims as necessary sacrifices for his perceived greater cause.

Re-envision by narrowing to abstract meanings

- In the final stages, Andersson re-envisioned the attack as his defining life act, a way to permanently inscribe his significance in history and society.

- Andersson’s envisioned meanings likely centered on becoming a “hero” or “avenger” through a violent act, seeing it as a way to achieve ultimate significance.

Realize meanings via goal-oriented strategizing & planning

- Enrolled in several math courses at Risbergska adult education centre, with the last one in May 2021 (Aftonbladet, 2025), potentially influencing his later target selection.

- The planning and preparation for the attack may have provided a sense of purpose and control previously lacking in his life.

- Began planning the attack, including the acquisition and preparation of weapons.

Phase 5: Extremist outcomes (Preparation and execution)

Extremist attitude

- Developed a complete embrace of a radical ideology that justified violence as a means to achieve significance (Kruglanski et al., 2019).

- The choice of an adult education center as a target might indicate resentment towards educational institutions and what they represent in terms of social integration (SVT, 2025; The Guardian, 2025).

Extremist intentions

- Decided to carry out a mass shooting at Campus Risbergska, a place he once attended.

- The possession of legal firearms and extensive preparation, including changing into military-style clothing before the attack, indicate a high level of commitment to his extremist beliefs (The Independent, 2025).

Extremist actions

- On February 4, 2025, Andersson arrived at Campus Risbergska around lunchtime, walked around briefly, then entered a bathroom with a guitar-like case (Aftonbladet, 2025).

- He changed into green military-style clothing and took out at least one weapon from the case (Aftonbladet, 2025; The Independent, 2025).

- Andersson carried three guns and a knife during the attack, indicating extensive preparation (The Independent, 2025).

- At least ten people were killed, and Andersson was found dead at the scene (ITV News, 2025).

- Six people were taken to the emergency department at Örebro University Hospital, with five described as seriously injured (ITV News, 2025).

- According to anonymous sources, Andersson reportedly spared certain individuals while shooting others (TV2, 2025).

- Police exchanged fire with Andersson during the incident (The Independent, 2025).

Attack Aftermath

- The attack is considered Sweden’s worst-ever mass shooting (The Guardian, 2025).

- Police conducted a large-scale search operation at Andersson’s residence, using drones and heavily armed officers (The Independent, 2025).

- Swedish King Carl Gustaf and Queen Silvia, along with Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson, visited the site and attended a remembrance service (The Guardian, 2025).

- All government buildings and royal palaces in Sweden flew flags at half-mast from 9am on February 5, 2025, to commemorate the shooting (The Independent, 2025)

Key Processes Throughout Radicalization

1. Narrowing of meaning types: Andersson appears to have focused increasingly on abstract types of meaning, dismissing self-oriented, hedonistic, or materialistic types (Vos, 2023).

2. Shift in approaches to meaning: There was likely a move towards a more rigid goal-oriented approach focused on carrying out his attack, as evidenced by his extensive preparation and choice of multiple weapons (The Independent, 2025; Vos, 2023).

3. Reappraisal: Andersson reinterpreted his life experiences and societal events through the lens of his extremist ideology, possibly viewing his unemployment and social isolation as justifications for violence (Park, 2010).

4. Practical realization skills: He developed new skills aligned with his extremist goals, such as planning the attack, changing into military-style clothing, and using multiple weapons (Kruglanski et al., 2019; The Independent, 2025).

5. Re-envisioning meanings: Personal and societal meanings were reconstructed to fit his new radical worldview, potentially seeing violence as a means to achieve significance or revenge against perceived societal injustices (Park & Folkman, 1997).

Summary of the Radicalization Process

Rickard Andersson’s journey from a socially isolated individual to a mass shooter illustrates the complex interplay of personal, social, and societal factors in the radicalization process. His academic struggles, long-term unemployment, and social isolation created vulnerabilities that, when combined with broader societal changes and exposure to extremist ideologies, led to a progressive embrace of violent extremism. The MOSAIC model helps us understand how Andersson’s quest for personal significance and meaning, in the context of perceived societal injustices and reinforced by online echo chambers, ultimately resulted in the tragic attack at Campus Risbergska.

Missed Opportunities in Andersson’s Case: A MOSAIC Model Perspective

Based on the MOSAIC model analysis of Rickard Andersson’s radicalization process, several critical opportunities for intervention were missed:

- Early Academic Intervention:

– Authorities failed to address Andersson’s severe academic struggles at Navets skolen, where he spent nine years without passing a single subject. A comprehensive educational support system could have provided personalized learning plans and additional tutoring to prevent his academic failure and subsequent feelings of inadequacy.

- Vocational Guidance:

– Despite Andersson’s interest in ice hockey and driving, there was no apparent effort to guide him towards vocational training or alternative career paths. Career counseling services could have helped him find meaningful employment or educational opportunities aligned with his interests.

- Mental Health Support:

– The reported mental health issues mentioned by relatives were not adequately addressed. Regular mental health screenings and accessible services could have identified and treated potential problems early on, potentially preventing his social withdrawal and vulnerability to extremist ideologies.

- Long-term Unemployment Intervention:

– Andersson’s lack of taxable income since 2014 should have triggered targeted job placement and training programs. The prolonged unemployment likely contributed significantly to his sense of alienation and search for alternative sources of meaning.

- Social Integration Programs:

– As Andersson became increasingly isolated, described as a “recluse” and “loner,” there were no apparent community-based programs to engage socially isolated individuals. Support groups or community outreach initiatives could have maintained social connections and prevented long-term isolation.

- Monitoring of Online Activities:

– While specific information about Andersson’s involvement with extremist networks is not available, authorities missed the opportunity to implement digital literacy programs or online intervention strategies that could have identified and addressed potential radicalization in digital spaces.

- Firearm Ownership Review:

– Despite Andersson’s mental health issues and long-term unemployment, his legal ownership of multiple hunting rifles was not reassessed. Regular check-ins or reassessments for firearm license holders could have flagged potential risks.

- Follow-up on Military Service Rejections:

– Andersson’s repeated rejections from military service were not followed up with alternative paths for civic engagement or purpose. This missed opportunity could have provided him with a sense of belonging and contribution to society.

- Meaning-Making Interventions:

– There was a lack of programs designed to help individuals like Andersson find positive sources of meaning and significance in their lives. Community projects or initiatives that allow individuals to contribute meaningfully to society could have fostered a sense of purpose and belonging.

- Cultural Integration Support:

– Given the changing demographics in Sweden and the rise of right-wing populism, authorities missed the opportunity to implement targeted programs addressing cultural anxieties and promoting intercultural understanding in Andersson’s community.

These missed opportunities highlight the importance of a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach to preventing radicalization. By addressing individual, social, and societal factors contributing to extremism, authorities could have potentially interrupted Andersson’s path to radicalization at various stages. The MOSAIC model emphasizes the need for early identification of risk factors combined with targeted interventions and support systems to reduce the likelihood of individuals turning to extremism as a means of finding meaning and significance in their lives.

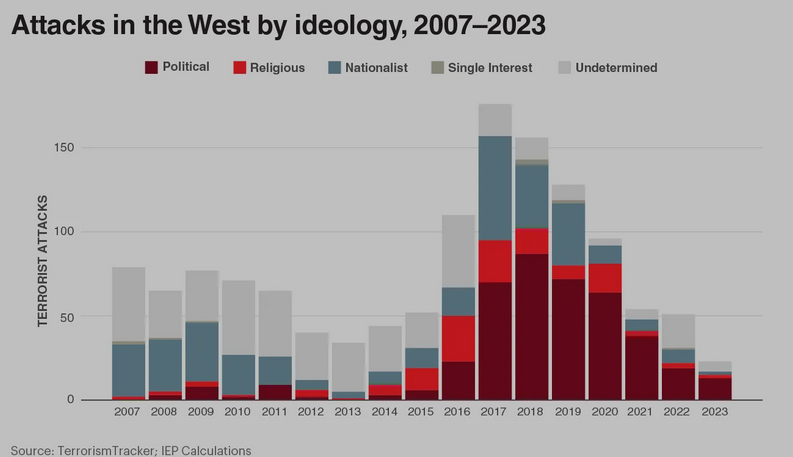

The Non-Uniqueness of Andersson’s Case: A Broader Perspective on Radicalization in Nordic Countries

While Rickard Andersson’s case is deeply troubling, it is important to recognize that his radicalization process follows patterns that are, unfortunately, not unique. The MOSAIC model reveals that Andersson’s journey towards extremism aligns with predictable patterns observed in other cases of radicalization, both in Sweden and globally.

Commonalities with Other Extremist Cases

- Quest for Significance: Like many other extremists, Andersson’s radicalization was driven by a fundamental need for personal significance and meaning (Kruglanski et al., 2019). His academic failures, long-term unemployment, and social isolation created a fertile ground for extremist ideologies that promised a sense of purpose and importance.

- Gradual Progression: Andersson’s radicalization followed the typical phases outlined in the MOSAIC model, from initial meaning foundations through to extremist outcomes. This gradual progression is a common feature in many radicalization cases, highlighting the importance of early intervention (Vos, 2023).

- Online Radicalization: While specific details of Andersson’s online activities are not available, the role of internet communities in fostering extremist beliefs is a well-documented trend in modern radicalization processes (Koehler, 2022).

- Response to Societal Changes: Andersson’s apparent resentment towards societal changes, particularly related to immigration and cultural shifts, mirrors broader trends of right-wing extremism in Nordic countries (Rydgren & van der Meiden, 2019).

Broader Trends in Nordic Countries

Andersson’s case connects to wider patterns of radicalization and violence in Nordic societies:

- Rise in Far-Right Extremism: Sweden and other Nordic countries have seen an increase in far-right extremist activities, often fueled by anti-immigration sentiments and perceived threats to national identity (Ravndal, 2018).

- Gang-Related Violence: While Andersson’s case is not directly related to gang culture, the increase in gang-related shootings in Sweden points to a broader issue of marginalized individuals seeking belonging and significance through violent means (Sturup et al., 2019).

- Lone-Actor Terrorism: Andersson’s attack fits into a concerning trend of lone-actor terrorism in Nordic countries, where individuals radicalize and plan attacks without direct organizational support (Schuurman et al., 2019).

Societal Factors Contributing to Radicalization Risk

The broader problems mentioned in research on meaning in life help explain why there may be many potential “Rickard Anderssons” in Nordic society:

- Lack of Meaning-Oriented Education: Educational systems often focus on academic and vocational skills without adequately addressing students’ need for meaning and purpose, leaving individuals like Andersson vulnerable to extremist narratives (Vos, 2023).

- Decline of Meaning-Centered Communities: The erosion of traditional community structures and the rise of individualism have left many without strong social support networks or shared sources of meaning (Martela & Steger, 2016).

- Intergenerational Disconnection: Secularization and rapid societal changes have disrupted the transmission of intergenerational meanings, leaving some individuals struggling to find their place in society (Vos, 2023, 2020).

- Increased Societal Complexities: Globalization and technological advancements have created a more complex world, making it challenging for some individuals to navigate and find a sense of belonging (Kruglanski et al., 2019).

- Economic Pressures: Issues such as decreasing social mobility and the phenomenon of “generation rent” create economic stress and uncertainty, potentially fueling resentment and vulnerability to extremist ideologies (Standing, 2011).

- Impact of Crises: Economic downturns, pandemics, and other societal crises can exacerbate feelings of powerlessness and loss of meaning, creating conditions ripe for radicalization (Kruglanski et al., 2022).

Conclusion: A Call for Comprehensive Approaches

Rickard Andersson’s case, while deeply tragic, is unfortunately not an isolated incident. It reflects broader trends of radicalization and extremism that stem from complex societal issues. The predictability of his radicalization process, as illuminated by the MOSAIC model, underscores the urgent need for comprehensive, society-wide approaches to addressing the root causes of extremism. By recognizing that Andersson’s case is part of a larger pattern, policymakers can develop more effective, holistic strategies to prevent radicalization and build more resilient, inclusive societies. The challenge lies not just in addressing individual cases, but in creating societal conditions where fewer individuals feel compelled to seek meaning and significance through extremist ideologies and violent actions.

Implications and Recommendations

Introduction

The tragic case of Rickard Andersson, culminating in the mass shooting at Campus Risbergska in Örebro, Sweden, on February 4, 2025, serves as a stark reminder of the critical need for effective radicalization prevention strategies. This comprehensive analysis explores the implications of Andersson’s case, focusing on how authorities can improve their models for identifying individuals at risk, the role of government policies, and the crucial importance of meaning-oriented education in preventing radicalization. By examining this case through the lens of the MOSAIC (Meaning-Oriented Social And Individual Change) model, we can derive valuable insights and recommendations for countering violent extremism.

Indications of Radicalization: Lessons from Andersson’s Case

- Narrowing Meaning Types

In Andersson’s case, we observed a clear focus on abstract types of meaning, dismissing self-oriented, hedonistic, and materialistic types. His fixation on perceived societal injustices and cultural threats indicates a narrowing of his sources of meaning.

Recommendation: Develop programs that encourage individuals to maintain a diverse range of meaning types, including personal growth, relationships, and everyday pleasures.

- Abstract Ideals Focus

Andersson’s radicalization process centered around abstract ideology, particularly related to anti-immigration sentiments and cultural preservation.

Recommendation: Provide alternative sources of meaning that are concrete and personally relevant, such as community service projects or skill development programs.

- Increased Search for Social Meanings in Extremist Groups

While Andersson was described as a “loner,” his radicalization likely involved seeking social connection through online extremist communities.

Recommendation: Create inclusive social programs that provide healthy alternatives for individuals seeking belonging and social identity.

- Decline in Critical Thinking and Intuitive Understanding

Andersson’s embrace of extremist ideologies suggests a reduced capacity for critical thinking and nuanced understanding of complex social issues.

Recommendation: Implement educational programs that foster critical thinking skills and media literacy from an early age.

- Rigid Conformism or Focus on Traditions to Find Meaning

Andersson’s attachment to a narrow view of Swedish culture and identity indicates a rigid approach to finding meaning through tradition.

Recommendation: Promote flexible and inclusive interpretations of cultural traditions that allow for adaptation and diversity.

- Goal-Oriented Focus

Andersson’s meticulous planning of the attack demonstrates a goal-oriented focus aligned with extremist ideals.

Recommendation: Provide alternative goal-setting frameworks that channel individuals’ drive towards constructive personal and community objectives.

- Increased Radical Engagement

While specific details are limited, Andersson’s progression to violent action suggests increased engagement with extremist ideas over time.

Recommendation: Develop early intervention programs that can identify and address signs of growing radical engagement.

- Persistent Unfulfilled Meanings

Andersson’s long-term unemployment and social isolation point to persistent unfulfilled meanings in his life.

Recommendation: Create support systems that help individuals find fulfillment through various life domains, including career counseling and social integration programs.

- Decline in Self-Oriented Meanings

Andersson’s case suggests a decline in self-care and personal development as he became more focused on abstract ideological goals.

Recommendation: Promote self-care, personal growth, and individual well-being as essential components of a meaningful life.

- Unstable Meaning-Making

Andersson’s radical shift from social withdrawal to violent action indicates unstable meaning-making processes.

Recommendation: Offer guidance and support for developing stable, positive sources of meaning that can withstand life challenges.

- Rapid Radicalization Progression

While Andersson’s radicalization likely occurred over time, the final progression to violence may have been rapid.

Recommendation: Enhance monitoring systems to detect sudden changes in behavior or ideology that may indicate accelerated radicalization.

- Increased Resistance

Andersson’s actions suggest a strong resistance to alternative perspectives that could have challenged his extremist views.

Recommendation: Develop dialogue-based interventions that gently introduce alternative viewpoints without triggering defensive reactions.

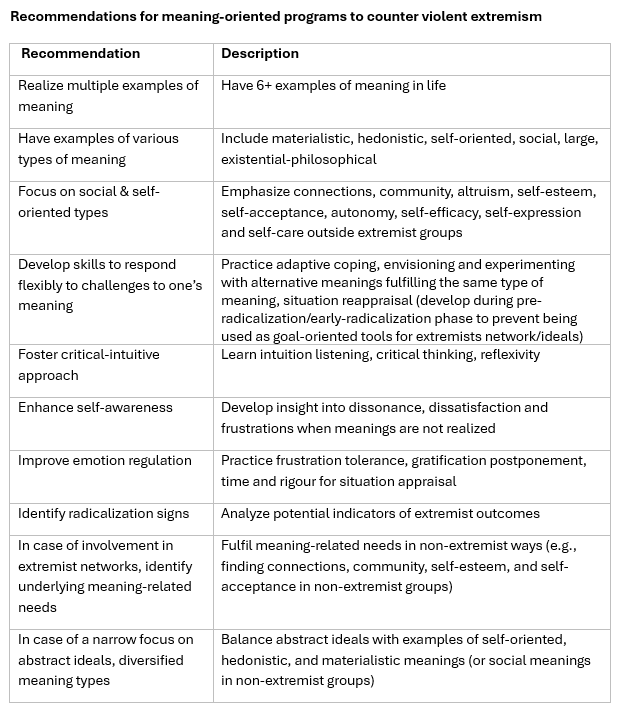

Recommendations for Meaning-Oriented Programs

- Realize Multiple Examples of Meaning

Andersson’s narrow focus on abstract ideological meanings highlights the need for diverse examples of life’s purpose.

Recommendation: Implement educational programs that expose individuals to at least six different examples of meaning in life, ranging from personal achievements to community contributions.

- Have Examples of Various Types of Meaning

Andersson’s case demonstrates the dangers of fixating on a single type of meaning.

Recommendation: Develop curricula that include materialistic, hedonistic, self-oriented, social, and existential-philosophical examples of meaning to provide a well-rounded perspective.

- Focus on Social & Self-Oriented Types

Andersson’s isolation and lack of positive social connections contributed to his vulnerability to extremist ideologies.

Recommendation: Create programs that emphasize connections, community, altruism, self-esteem, and self-expression to build resilience against radicalization.

- Develop Skills to Respond Flexibly to Challenges

Andersson’s inability to cope with academic failures and unemployment in constructive ways points to a lack of adaptive coping skills.

Recommendation: Teach adaptive coping strategies, including envisioning alternative meanings and situation reappraisal techniques, particularly during the pre-radicalization and early-radicalization phases.

- Foster Critical-Intuitive Approach

Andersson’s embrace of simplistic extremist narratives suggests a lack of critical thinking skills.

Recommendation: Implement educational programs that teach intuition listening, critical thinking, and reflexivity to enhance individuals’ ability to navigate complex social issues.

- Enhance Self-Awareness

Andersson’s case indicates a lack of insight into his own dissatisfactions and frustrations.

Recommendation: Develop programs that help individuals recognize and address their unmet needs and frustrations in healthy ways.

- Improve Emotion Regulation

Andersson’s violent outburst suggests poor emotion regulation skills.

Recommendation: Offer training in frustration tolerance, gratification postponement, and emotional appraisal to help individuals manage intense emotions without resorting to extremism.

- Identify Radicalization Signs

The failure to recognize Andersson’s progression towards extremism highlights the need for better awareness of radicalization indicators.

Recommendation: Train community members, educators, and mental health professionals to analyze potential indicators of extremist outcomes.

- Address Underlying Meaning-Related Needs

Andersson’s case demonstrates how unmet needs for belonging and significance can drive individuals towards extremism.

Recommendation: Develop programs that fulfill meaning-related needs in non-extremist ways, such as community service initiatives or mentorship programs.

- Diversify Meaning Types

Andersson’s fixation on abstract ideals underscores the importance of a balanced approach to meaning.

Recommendation: Create interventions that balance abstract ideals with examples of self-oriented, hedonistic, and materialistic meanings, or promote social meanings in non-extremist groups.

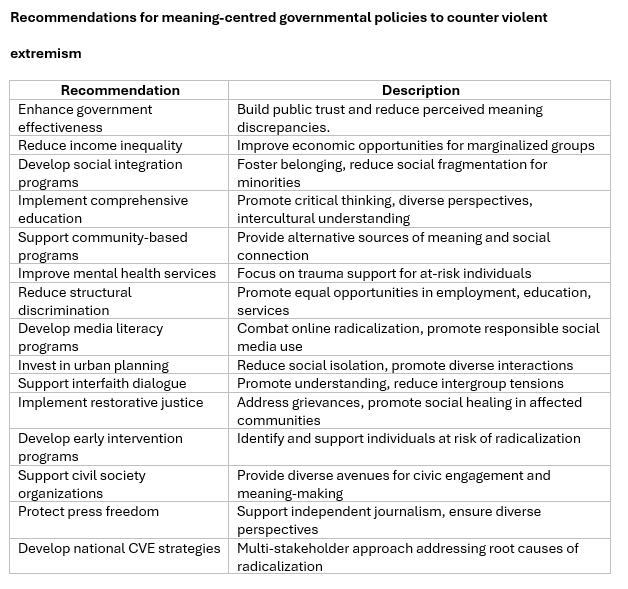

Recommendations for Meaning-Centered Governmental Policies

- Enhance Government Effectiveness

Andersson’s disillusionment with society suggests a lack of trust in governmental institutions.

Recommendation: Implement policies that build public trust and reduce perceived meaning discrepancies, such as transparent communication initiatives and responsive public services.

- Reduce Income Inequality

Andersson’s long-term unemployment likely contributed to his sense of alienation and resentment.

Recommendation: Develop policies that improve economic opportunities for marginalized groups, including job creation programs and progressive taxation.

- Develop Social Integration Programs

Andersson’s isolation highlights the need for better social integration initiatives.

Recommendation: Create programs that foster belonging and reduce fragmentation for minorities, such as community-based cultural exchange events.

- Implement Comprehensive Education

Andersson’s academic struggles and subsequent attack on an educational institution underscore the importance of effective, inclusive education.

Recommendation: Reform educational systems to promote critical thinking, diverse perspectives, and intercultural understanding from an early age.

- Support Community-Based Programs

The lack of community intervention in Andersson’s case points to the need for stronger local support systems.

Recommendation: Fund and promote community-based programs that provide alternative sources of meaning and social connection.

- Improve Mental Health Services

Andersson’s reported mental health issues suggest a gap in mental health support.

Recommendation: Expand access to mental health services, with a focus on trauma support for at-risk individuals.

- Reduce Structural Discrimination

Andersson’s resentment towards societal changes may have been fueled by perceived discrimination.

Recommendation: Implement policies that promote equal opportunities in employment, education, and services for all members of society.

- Develop Media Literacy Programs

Andersson’s susceptibility to extremist narratives indicates a need for better media literacy.

Recommendation: Create comprehensive media literacy programs to combat online radicalization and promote responsible social media use.

- Invest in Urban Planning

Andersson’s social isolation might have been exacerbated by urban design that doesn’t foster community interaction.

Recommendation: Develop urban planning strategies that reduce social isolation and promote diverse interactions within communities.

- Support Interfaith Dialogue

Andersson’s case highlights the need for better understanding between different cultural and religious groups.

Recommendation: Promote interfaith and intercultural dialogue initiatives to reduce intergroup tensions and foster mutual understanding.

- Implement Restorative Justice

The lack of alternative conflict resolution methods in Andersson’s case suggests a need for restorative justice approaches.

Recommendation: Develop restorative justice programs that address grievances and promote social healing in affected communities.

- Develop Early Intervention Programs

The failure to intervene early in Andersson’s radicalization process underscores the need for proactive measures.

Recommendation: Establish early intervention programs to identify and support individuals at risk of radicalization before they progress to violent extremism.

- Support Civil Society Organizations

The absence of strong civil society engagement in Andersson’s case indicates a missed opportunity for prevention.

Recommendation: Provide support and resources to civil society organizations that offer diverse avenues for civic engagement and meaning-making.

- Protect Press Freedom

The role of media narratives in shaping Andersson’s worldview highlights the importance of a free and responsible press.

Recommendation: Safeguard press freedom while promoting responsible journalism that presents diverse perspectives on social issues.

- Develop National CVE Strategies

Andersson’s case reveals the need for comprehensive, national-level approaches to countering violent extremism.

Recommendation: Develop multi-stakeholder national strategies that address the root causes of radicalization through coordinated efforts across various sectors of society.

Conclusion

The tragic case of Rickard Andersson serves as a powerful call to action for implementing comprehensive, meaning-oriented approaches to preventing radicalization and violent extremism. By adopting the recommendations derived from the MOSAIC model and applying them across educational, community, and governmental domains, we can work towards creating societies that are more resilient to extremist ideologies and more fulfilling for all their members.

The key to success lies in addressing the fundamental human need for meaning and significance in constructive ways. By providing diverse sources of meaning, fostering critical thinking, promoting social integration, and addressing systemic inequalities, we can create an environment where individuals like Andersson are less likely to turn to extremism as a means of finding purpose and belonging.

As we move forward, it is crucial that policymakers, educators, mental health professionals, and community leaders work together to implement these strategies. The lessons learned from Andersson’s case, viewed through the lens of the MOSAIC model, offer a roadmap for building a more inclusive, understanding, and meaningful society – one that can effectively counter the appeal of extremist ideologies and prevent future tragedies.

References

ACLED. (2024). Annual Report on Global Conflict Trends.

Aftonbladet. (2025). Exclusive interview with Rickard Andersson’s relative.

Avaz.ba. (2025). Otkriven identitet napadača iz Švedske: Bio je izuzetno čudan.

BBC News. (2025). Sweden shooting: What do we know about the suspect?

Bhui, K., Everitt, B., & Jones, E. (2014). Might depression, psychosocial adversity, and limited social assets explain vulnerability to and resistance against violent radicalisation? PLoS One, 9(9), e105918.

Corner, E., & Gill, P. (2015). A false dichotomy? Mental illness and lone-actor terrorism. Law and Human Behavior, 39(1), 23-34.

Expressen. (2025). Rickard Andersson: The path to extremism.

Global Activism Trends Institute. (2022). Youth Political Engagement Survey.

ISRD4. (2024). International Self-Report Delinquency Study (ISRD4). Institute of Criminology and Legal Policy, University of Helsinki.

ITV News. (2025). Sweden’s ‘worst mass shooting’ leaves at least 11 dead at adult education centre.

Koehler, D. (2022). Online radicalization: Myths and realities. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 45(1), 1-14.

Kruglanski, A. W., Bélanger, J. J., & Gunaratna, R. (2019). The three pillars of radicalization: Needs, narratives, and networks. Oxford University Press.

Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531-545.

National Gang Center. (2024). National Youth Gang Survey Analysis. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U.S. Department of Justice.

OECD. (2015). In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. OECD Publishing.

Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 257-301.

Park, C. L., & Folkman, S. (1997). Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology, 1(2), 115-144.

Price Waterhouse Coopers PwC. (2024). The Global Youth Outlook. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.com/m1/en/publications/the-global-youth-outlook.html

Ravndal, J. A. (2018). Right-wing terrorism and violence in Western Europe: Introducing the RTV dataset. Perspectives on Terrorism, 12(6), 1-15.

Rydgren, J., & van der Meiden, S. (2019). The radical right and the end of Swedish exceptionalism. European Political Science, 18(3), 439-455.

Schuurman, B., Lindekilde, L., Malthaner, S., O’Connor, F., Gill, P., & Bouhana, N. (2019). End of the lone wolf: The typology that should not have been. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 42(8), 771-778.

Standing, G. (2011). The precariat: The new dangerous class. Bloomsbury Academic.

Sturup, J., Rostami, A., Mondani, H., Gerell, M., Sarnecki, J., & Edling, C. (2019). Increased gun violence among young males in Sweden: a Descriptive National Survey and International Comparison. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 25(4), 365-378.

Svallfors, S. (2016). Politics as organised combat – New players and new rules of the game in Sweden. New Political Economy, 21(6), 505-519.

Swedish Police Authority. (2025). Official statement on the Örebro shooting.

SVT. (2025). Rickard Andersson: The path to extremism.

The Guardian. (2025). Shooter at Örebro school had taken classes there, reports Swedish media.

The Independent. (2025). Rickard Andersson: Who was the Sweden school shooting suspect.

TV2. (2025). Kilder til Aftonbladet: Massemorderen skånet enkelte.

Vos, J. (2020). The Economics of Meaning in Life. University Press of America.

Vos, J. (2021). The Psychology of COVID-19: Building Resilience for Future Pandemics. SAGE Publications.

Vos, J. (2022). Meaning in Life: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Practitioners. SAGE Publications.

Vos, J., et al, (2026). (Articles under review.)

Vos, J., Roberts, R., & Davies, J. (2019). Mental Health in Crisis. SAGE Publications.

https://www.dagbladet.no/nyheter/dette-er-den-mistenkte-skytteren/82632131